Andy McCourt has been involved with graphic equipment for over 30 years. He has held executive positions involving the supply of both new and used machinery. In 1993 while stationed in London, he helped Benny Landa launch the Indigo E-Print digital printer to the world at Ipex, for which he was on the marketing committee and also Asia-Pacific Project Manager, increasing Ipex attendance from that region by 120%. For 2 years he worked with the industrial division of Australia's largest Valuation and Auctioning firm, Grays, in both onsite and online asset disposals of major printing and packaging equipment.

Always a contributor to the graphic arts trade press, he is today the editor of Print21 - the official journal of the Printing Industries Association of Australia and consults to several prominent suppliers to the printing, packaging and publishing industries. A veteran of 8 drupas and 6 Ipexes, plus numerous other industry events around the globe, he lives in Sydney and stays fully informed on happenings with graphic arts technology, new media - and machines.

Thieme superwide format screen printing line

“…Shall thy bounds be set” so goes the song Land of Hope and Glory. When it comes to wide-format digital printing, while the width boundary seems set at 5 metres max – the scope for market growth appears almost limitless. But what exactly is ‘wide format printing’?

Three drupas ago it still referred to oversize offset presses, such as those from KBA and Manroland sheetfed. KBA appear to be kings of wide, or XXXL, format in offset with the Rapida 205, printing a massive 1510mm x 2050mm sheet. The largest sheetfed press in the world is reportedly a 7-colour KBA Rapida 205 at National Posters in Chattanooga, USA. That’s a lot of choo-choo at 272 tonnes and 30 metres long.

Not far behind in sheer size is Manroland sheetfed with the 900XXL capable of 1300mm x 1850mm sheets in the ‘Format 8’ configuration. Such oversize presses are typically sold into the packaging sector, with 0.6mm thickness being the norm and a 1.2mm corrugated option available.

Heidelberg has forayed into XXL size presses with the XL145cm and 162cm models but has so far not ventured into KBA’s 185cm and 205cm sector. With such presses running at 12,000-18,000 sph, it goes without saying that you need a lot of large sheet throughput – posters, POP, packaging flats eg – to keep them busy.

Screen printing has probably suffered more from the advent of these supersized offset litho presses, but Thieme still holds its ground in screen process with the 5095XL capable of sheet sizes up to 2000mm x 3000mm and thicknesses up to 10mm. The vibrancy and coatings possible with screen process also goes a long way to keeping this great process alive.

A 5 metre EFI Vutek GS5000 – Vutek pioneered superwide format digital printing

But what about that 5 metre wide printing? This comes from the newest wide format process and no prizes for guessing – it’s digital, and inkjet in particular. It started with a company named Vutek in the early 1990s (now owned by EFI), although before that US billboard specialist MetroMedia Technology (MMT) developed its own supersize printer using a paint-nozzle system and huge rotating drum. Vutek pioneered super wide format digital printing and were joined in 1994 by an Israeli company Idanit, later to become Scitex Vision before acquisition by Hewlett Packard in 2005.

Another Israeli company NUR Macroprinters entered the market, also bought by HP, in 2008. All together, these pioneers of digital inkjet production up to 5 metres wide revolutionised the outdoor billboard market, where huge signs were once knows as ’48-sheeters or 96 sheeters’ because the screen or offset-printed sheets were pasted up by riggers who had to ‘marry-up’ the right sheets in the right place, like a mosaic. A 96-sheet site was about 3 x 12 metres and required 24 sheets.

As 3 and 5 metre wide digital inkjet machines gained popularity, these billboard super-sites became much better quality (there were no mis-registrations or peeling), and easier to set up. New materials such as outdoor PVC and canvas enabled one-piece supersize billboards to be laced up and stretched on metal frames, lit and changed easily – billboard ‘skins.’

Lateral markets developed such as truck-side curtains; building shrouds, mesh for scaffolding, theatrical backdrops, fence advertising and even helicopter-towed giant signs. New entrants entered the printer market with names such as Roland DG, Mutoh, Fujifilm, Matan, Gandy, Mimaki, Agfa and Jeti. Many Korean and Chinese printers came available, of widely varying quality. Some found 3.2 metres was wide enough and didn’t offer 5 metre models; 2.5 metres also proved popular for bus shelter signs, back-lit panels, POP and airport advertising.

The Inca Onset Q50i flatbed UV -this one installed at Imprint, Newcastle, UK

The nett result is that the wide and super-wide format print sector has boomed, growing at 6.69% CAGR up to 2020 according to the article at "Recharge Asia". It is estimated to be worth almost USD$1 billion annually in printer sales alone.

Of course, this means that used machines are starting to find their way onto markets and these can represent a low-cost entry into the burgeoning sector. Things to watch out for are printheads; age and condition. The bulk of the cost of a superwide format printer is in the printheads and carriage assembly. Machines can have up to 512 piezo printheads costing $2-$4,000 each to replace.

Truck side curtains become mobile advertising with digitally-printed graphics.

Depending on the type of ink used (aqueous, solvent, UV-cure or Latex); printhead life is affected by the degree of aggression of the ink. I have seen 7-year old printheads under a microscope where the nozzles look like volcano craters – yet they still eject ink droplets and the banners or billboards can pass for distance-viewed images. They need regular cleaning so maintenance history is critical too.

Printhead manufacturers include Xaar, Fujifilm Dimatix (Spectra), Ricoh, Konica Minolta, Toshiba Tec, Kyocera and others. They are all of the piezo kind in superwide, with the exception of HP’s Latex printheads which are their own and thermal.

The media transport system, belts, gears, servo micro motors, need to be in good shape otherwise you are sure to get banding. Good inkjet roll printing is all about the synch between media transport in the x axis and a ‘flying shuttle’ printhead array in the y axis; sloppy gears or belts will affect that.

As with offset presses, stick with good brands for used wide format printers – HP Scitex, EFI Vutek, Fujifilm Acuity, Inca Digital, Screen Truepress, Canon/Océ, SwissQprint etc. Some of the cheaper superwides are rarely built well enough to survive a second owner.

There is plenty of support out there and plenty of market opportunity to diversify your print business by going superwide!

Offset Litho printing has certainly been ‘Cinderella’ at the world’s digital printing ball, as evinced at the recent drupa trade fair where for the first time HP was the largest exhibitor, Heidelberg’s area was reduced compared to previous expos and the glitziest, largest singing-and-dancing exhibition stands were from companies such as Xerox, Canon, Konica Minolta, Ricoh and of course Landa Nanotech.

Nevertheless, for those with perception that cuts through hype and techno-babble, there were identifiable offset trends that bring the ink-plate-press-print method of printing well up to date with digital workflows, automation and ‘hands-off’ printing. Even older presses can be retrofitted with the latest digital goodies such as CIP3 closed-loop automated ink duct control linked to prepress, such as that from Printflow based in the Slovak Republic (www.printflow.eu »)

The ‘big iron’ of offset is not about to go away anytime soon – in fact demand is on the increase again

Overall print volumes may have not fully recovered from the GFC crash in 2008

In 2015, but all quality research points to a global market value of around USD$825 billion and growth in volume and monetary terms of around 2% per annum up to the year 2020 (read more here »). While digital print accounted for 13.9% of all print and printed packaging in money terms, the same research estimates that it produces just 2.7% of the volume. Even by 2020, smitherspira estimates digital will have reached just 3.4% or total print volume.

This means that the big iron offset presses from Heidelberg, manroland, KBA, Komori, RMGT (Ryobi-Mitsubishi), Shinohara, Sakurai, Presstek and Goss will be producing most of the world’s print for a long time yet. Alongside these newer models will be a sizeable number of legacy machines traded on the global used equipment market.

Heidelberg estimates that for every new fully-automated press capable of 18,000 sheets per hour it installs; two or three older presses are removed. These machines need to find new homes, in their own country or in others where the costs of full automation are high or the labour costs are lower.

Another factor influencing the adoption of digital in developing markets is lack of support infrastructure. Digital machines, as wondrous as they are, require a much higher level of supplier technical support. Offset presses can be worked on by engineering-trained operatives but if a motherboard goes down on a digital press; its down until a replacement is fitted.

In some markets, such as narrow-web for labels, digital press sales are outstripping conventional flexo-screen-gravure label press sales. However, it must be kept in mind that those big-iron flexo etc presses are printing very long runs and it takes several digital narrow web devices to do what one fast flexo press can accomplish. A close look at the digital press installations reveals that the bulk of them are in fact supplied with ‘big iron’ converting! Not digital at all. The die-cutting, foiling, embossing, laminating, stripping, coating and rewinding, while digitally-controlled, is performed in the traditional way.

Back to offset litho. Advances in prepress (CtP in particular), UV curing, auto plate changing, auto clean-up and dampening along with CIP2, JDF and workflows have revitalised ‘big iron.’ Also at drupa 2016, Heidelberg were demonstrating live plate changes on an SX106-8 press where all 8 plates were changes three times in eight minutes! This makes 100-sheet jobs viable and this can compete with digital in all but variable content.

Such futuristic implementation of offset means that some printers are upgrading quite recent presses to gain the productivity benefits of the latest generation. This in turn translates into great offers and saving for buyers of 3 to 8 - year old presses and older. In fact, such as press, 2014, as the Heidelberg 8-colour mentioned above is currently on offer on this very site ».

50 years ago this was high-tech.

Should it be your next investment???

One of the marvels of older big iron machinery is just how durable the demand is. A recent auction in Australia where the printer was closing down, featured offset, digital and letterpress equipment. Remarkably, the most intense initial interest was for the letterpress equipment! Letterpress has become a little like vinyl records:- it’s being rediscovered for its beautiful tactile qualities, embellishments and gravitas. Wedding invitations printed by letterpress are the ‘in’ thing around the world. The British Caslon/Adana company has even seen fit to re-introduce manufacturing of small letterpress machines 25 years after production ceased!

Original Heidleberg T-Platen (T is for ‘Tiegel’ in German, meaning windmill) 10” x 15” presses cost around £1,000 in 1960 and they can easily sell for the same amount or more today. One in the Australian auction fetched AU$2,800 (£1,700). A larger GTP Platen converted for hot foiling and die-cutting was sold for AU$9,700 (£6,000).

Even 40-50 year old Heidelberg SB, SBD and KSB cylinder presses are in demand as die-cutters due to their ability to deliver high pressure on a narrow area. Some have foiling conversions. In parts of the world they are still heavily use in print production as the supply of trained operators is good.

What keeps the heavy metal presses in demand is the excellent engineering that enables them to keep performing the function they were built for, or be adapted to something else. Nebiolo single colour Invicta machines for example, convert well to UV spot and flood coating devices with new copper rollers and a UV tunnel at the end.

But undoubtedly the main thrust of the market is for good, low impression well-maintained multicolour offset presses and, if they are post 2000, there’s a good chance they will fit into any IT workflow and even if earlier they may be retrofittable with modern automation luxuries such as ink control.

The industry loves its bits and bytes, but is not ready to wave goodbye to heavy metal big iron anytime soon!

The processing line is another consideration

Not so long ago, Prepress was a diverse mix of skills, machines and systems that were so significant that they warranted their own international trade fair – Imprinta, the sister show held in-between drupas. Prepress equipment in the old analogue world meant that equipment for film exposing, scanning, typesetting, stepping up, combing, retouching, projecting and proofing had to be very precise – together with the skills of the operators. Hundreds of new businesses started up providing just scanning, film separations and combining, and proofs. It was profitable, in-demand and distinctly separated from plate burning and printing.

That entire industry was progressively wiped out by advances in digital, initiated by Prepress giants such as Scitex, Linotype-Hell, Screen, ICG, Quantel and Crosfield, with ‘high-end’ page make up systems, scanners and imagesetters. 1984 and the Apple Mac with PageMaker saw the beginnings of the Postscript revolution and DTP, which was in turn to wipe out most of the Prepress giants. A case of a little fish eating a bigger one?

Throughout the 1990s, the pace of Prepress digital change accelerated as DTP and Postscript surged ahead. Then, at the Seybold show, San Francisco in 1994, an unheard of company, Creo, showed a large box it had developed in conjunction with the world’s largest printer, RR Donnelly; that could make plates from Postscript data without film.

Film imagesetters had paved the way by combining typesetting and images, fully imposed, from design data and making just one set of plate-ready film separations. Now, with what became known as Computer-to-Plate, film was bypassed altogether and plates could be made directly, ready for mounting onto presses. PDF has made it even simpler.

It took a while for the lasers driving CtP to become perfected but, drupa 2000 became known as the ‘CtP drupa’ and a mad rush to manufacture this exciting technology began. Imprinta – the Premedia show – was effectively dead as all that it offered had been subsumed into drupa. Established prepress names such as Screen, Kodak, Linotype/Heidelberg, Fujifilm, Agfa, Creo-Scitex and Crosfield were joined by new names such as Highwater, Basys, Cymbolic Science, ECRM, Lüscher, Krause, Presstek, Autologic, Purup, Barco, Mitsubishi, Xanté and also by film imagesetter manufacturers seeking to replace their dwindling markets by imaging onto polyester plates. Later came inkjet platemakers from Epson, Glunz & Jensen, Kimo and others for short-run plates.

Once digital cameras exceeded 2 megapixels, the writing was on the wall for rotary film separation scanners from Crosfield, Screen, Hell, ICG and so on. Today there are hardly any left in operation as high-resolution RAW files and jpegs go directly into digital workflows. Scanners, flatbed and rotary, are handy to have sometimes when a hard copy photo or transparency comes in.

Today, Prepress hardware is basically computers, software, a CtP device and inkjet proofer. Everything else is software – Adobe Creative Suite, Rips from people like Harlequin, Xitron, Esko’s Artios for packaging – and workflows incorporating colour management to ensure accurate reproduction.

Oh, there are a few peripherals still – plate punches, densitometers, spectrophotometers and a small quantity of film is still used in Flexo and Screen Prepress, requiring exposure devices but, to all intents and purposes, graphic arts film in the west is virtually extinct. Konica, DuPont and Mitsubishi have ceased production, only Fujifilm, Agfa and Kodak continue with Rapid Access films and there are smaller manufacturers in South America and China. Film is still widely used in parts of the world such as S. America, Africa, India and China.

For the majority of printers today, buying used Prepress means buying CtP, a plate processor, the Rip to drive it and maybe the workflow behind it. It is a mature technology already, with past debates about the differences between internal or external drums, red or blue lasers, violet or thermal plates, decidedly passé.

The R&D focus of the remaining offset CtP manufacturers is in speed, power use and laser reliability as LED and laser diodes have replaced old style lasers. Plate processing lines are mostly linked to the CtP setter and designed to reduce water and chemical use. Of the dozens of CtP manufacturers when the technology was new, the mainstays today are Screen, Heidelberg, Kodak-Creo, Fujifilm, Agfa and the Chinese Cron. For Flexo CtP, Dupont’s Cyrel Fast, Esko’s CDI, Lüscher’s Flexline, MacDermid and Screen’s PlateRite offer the pathway for digital flexo plates and gravure has long been filmless with direct-engraving cylinder machines from Hell Gravure, Ohio, Daetwyler and Think Labs.

A typical B1 CtP setter - this one a Screen PlateRite

New CtP prices have tumbled, meaning that used devices offer very good value. A quick look on pressXchange.com shows around 115 CtP devices on offer from very good manufacturers.

The first step is to decide what size CtP you need for your press/es:

B3 or 2-up (in A4/letter pages)

B2 or 4-up

B1 or 8-up

VLF which can be 16, up to 48-up for big web presses and packaging

Colour management is critical in a good CtP workflow environment

Since you can’t proof economically from CtP plates you will need some kind of proofing device. These are usually Epson or HP inkjet printers hooked up to either the Rip data or separate proofing software such as GMG, Oris, EFI etc. The printers are profiled and matched to press output. More and more printers are making do with soft proofing on-screen but these monitors need to be high-quality calibratable, such as the Eizo ones.

Ask questions about the age of the Laser and what type it is. Older lasers are very expensive to replace, later ones use LEDs and diodes and last longer and are cheaper. A service record is handy, as is the plate count of number of plates imaged. Red or violet laser?? This will dictate what kind of plates you use. The red-end lasers (830nm) usually image only thermal plates, which require less processing. At the violet-end of the spectrum (470nm) the barely-visible blue laser is for violet-sensitive plates and these are typically silver-rich and can print longer press runs. There are also processless plates that wash-out on the press using fount solution, such as Fujifilm’s Superia Pro T-3. If you are attracted to these plates, make sure the CtP can be set up to image them as they need more power.

You can’t just pick up a CtP device, move it and plug it in again. The drum and laser carriage are very sensitive instruments and must be properly locked down before transport. Allow a bit extra for a technician to do this

Convenient extras can save time and money hunting around. These can include multiple plate loading cassettes, bridges to processors, the processor itself, plate stackers and maybe a plate dot reader or densitometer.

If you are moving from a film/print down system to CtP, you will be making plates in a fraction of the time, so a speed of, say 12 plates per hour at 2400 dpi is probably plenty unless you are a very busy shop. 24 pph is better and even the latest new CtPs run at maximum 70 pph.

CtP, colour management and workflow is basically all of modern Litho Prepress – and it needn’t cost the Earth to get into it!

A Duplo 600i booklet making line with single 10-bin tower. More towers can be added

If a printer has a bottleneck, I usually lay odds of London-to-a-brick-on that it’ll be in the finishing department. Presses run at up to 18,000 sheets per hour, but most finishing equipment struggles to keep up with the pace.

Unless you are a mega-finisher with top-end Muller Martini or Kolbus lines, chances are that jobs hang around in the bindery for much longer than they were in the press hall. Digital web presses are emerging with inline finishing that can almost keep up with the speed of the press, but more often than not, I see digital book printers printing roll-to-roll and finishing offline.

This is one reason why good used finishing equipment is always in demand; it adds a buffer for the busy times, keeps jobs in-house instead of being outsourced (not that outsourcing is always a bad thing).

Trade binder-finishers are able to offer a plethora of services that no general commercial printer could replicate economically. Wire-O, perfect, PUR, section-sewn, saddle stitch, hole-punched, half-Canadian and full Nelson are just some of the things they have to wrestle with. Then there’s Coptic binding (4,000 years old!) and the exquisite Japanese bind – both sewn. Newfangled screw-post binding is rather ugly, but to each his or her own.

There are also several proprietary binding methods for documents such as GBC’s (now Neopost) Velobind which uses a plastic strip with pins to secure the covers and text pages. It makes redacting of embarrassing government pages rather difficult.

Add to bindery, the need for folding, creasing, scoring, perforating, die-cutting and embellishing and you have a multitude of value-add opportunities for plain old sheets. It’s something that digital media on an iPad just can’t replicate. The snick of a perforated tear-off coupon; although I do so look forward to seeing the first perforated tablet device.

Folders can be given new life with new rollers, belts and vacuum wheels (MBO shown)

So, finishing is good; finishing is value-add and finishing equipment is in-demand. It’s an area where digital has thus far made only small inroads with devices like the Scodix and JetVarnish digital embellishers, Highcon’s laser creaser-cutter and Landa’s Metallography. Intelligent digital touch-screen controls and barcoded job memory have certainly become the norm but they are still controlling mechanical functions such as trimming, folding, scoring, collating and stitching

A quick look at pressXchange shows that there are 63% as many bindery and finishing machines for sale as there are sheetfed presses – the second-largest category by far. Folders comprise the largest sub-category with well know brands such as Stahl, MBO, GUK, Horizon, Hunkeler and Shoei represented in many configurations and specialist folders such as the Herzog & Heyman pharma-folder also coming up now and then.

When buying used folders and folding lines, its always a good idea to look carefully at the condition of the rollers, belts and vacuum wheels as these are the parts that wear quickest. There are plenty of third-party roller and wheel suppliers so it is not the end of the world if they need replacing – so long as the price of the machine is right.

Even older Muller Martini stitcher-gatherers are in demand – at the right price

I once examined several used MBO folders and stackers that had undergone refurbishment by former MBO technicians. Every little rubber part had been replaced, bearings checked and even blue paint re-applied in places. “They are like new” I commented. “Better than new now,” said the proud tech.

In the SRA3 format, collate-fold-stitch-trim lines are always in demand and the big brands are Horizon, Duplo, CP Bourg, Watkiss with smaller machines from Nagel, Plockmatic and others. Again, condition depends of amount of use and maintenance but something to look out for is availability of main circuit boards on STF lines over about eight years old. If the main circuit board is malfunctioining, it could mean a worldwide search for an identical replacement one.

Perfect binding lines are driven by the demand for magazines, catalogues, annual reports and books. Here, for the right product with automation and the ability to bind short and long runs cost-effectively; demand is still strong. I recently dealt with a 10-year old Wohlenberg city-e 6000 with 20 clamps, PUR and full WST Opticontrol. Costing over $2 million new, it could still attract buyers at well over $500,000 and was snapped up even before listing.

The most recognizable name in long stitching/binding/inserting lines is Müller Martini with even 30+ year old 221s and 235s finding buyers. The Swiss company is still going strong and showed fully automated end-to-end book lines at drupa that included a digital print station.

Never miss the cut! Good brand guillotines sell well. (Polar shown)

Die-cutters never seem to go out of style, with Bobst, another Swiss company, being king in this area. A die-cutter performs one task repeatedly: bringing down a heavy platen fitted with a knife forme, onto corrugated or fibre board to die-cut boxes and POP displays. Because of the extra heavy engineering, we see Bobst die-cutters even from the 1950s and 60s coming up and selling, although the more recent programmable models that may have extra functionality such as foiling and gluing are popular.

Print finishing is a diverse and complex field but engineers have come up with equipment for every conceived possibility. Operating the right kind of bindery-finishing department can set a print business apart from the competition, open up new markets; for example maps that open in one hand movement, multi-part mailers with glued return envelopes, A4 conference folders with pouches and so on.

There is plenty of used bindery and finishing equipment out there at big savings from buying new – like any used purchase inspect and verify condition but the chances of a good-value profit-making purchase will put more of that other kind of ‘folding stuff’ in your pocket!

As the world of printing shifts from a post-industrial and information revolution manufacturing process, to a networked digitized service; so the nature of the tools we use changes.

It’s a slow process and rightly so – it would be foolhardy to ‘arrive’ in the future before it is really here. However, the future’s tendrils are already feeling their way into mainstream print production, as was clearly demonstrated at drupa 2016 held in Germany in June. If not all-out digital presses everywhere, what we saw was hybridized models from big manufacturers such as KBA, Heidelberg, Komori, Miyakoshi-Ryobi. Even recognized all-digital manufacturers such as HP, Canon and Landa have turned to heavy-metal press and finishing manufacturers for their sheet and reel paper handling – an engineering art that has been refined over 150 years of progress since hand-feeding was deemed too slow.

The move up to digital B1 sheet-size presses and wide webs – up to 2.6 metres in the case of the hybrid KBA-HP corrugated liner machine – combined with higher speeds poses vastly more physical and chemical challenges to be overcome; challenges that were admirably overcome in the non-digital printing world. Since all digital printing can trace its roots back to photocopiers – those annoying devices that sat in offices and quick print shops waiting for burly, unshaven technicians to call and un-jam them, while in the process displaying far too much gluteus maximus cleavage – since this is in digital printing’s DNA, it has taken a while for the manufacturers to come to terms with the industrial nature of high volume printing, packaging and publishing.

At first, they tried to solve the paper handling problems themselves but now, have turned to the engineers, designers and metallurgists who have known how to handle sheets and reels for two generations or more. “Paper jam in tray number two” is not acceptable in industrial-scale printing, especially when it happens five times a day.

Which brings us to today’s advanced digital presses and why they are not commanding the resale values we are accustomed to with offset, flexo and gravure.

This 2008 HP Indigo 5500 probably had a capital value of USD$400,000-$500,000 when new; today between $30,000 and $50,000, without a maintenance and click contract. Always speak with the manufacturer about continuing in-place service contracts.

When you buy into a digital press, you are not just buying the atoms, molecules and assembly. Our wonderfully engineered presses from Heidelberg, manroland, KBA, Ryobi-Mitsubishi, Komori, Goss and so forth are essentially machine tools. They are capable of standing alone and being traded at market values because the operational ‘intelligence’ is provided by humans. It’s just like cars and trucks: a vehicle can be sold and re-sold many times over and never with a driver ‘thrown in’ – the new owner provides the operational intelligence and skillset.

With digital presses, the business model involves a close relationship with the vendor that is almost marriage-like. The technology is so complex that, without full vendor support, a print business will soon grind to a halt because OPCs, fusers, lasers, printheads, rips, drivers and workflows are not totally under the control of the operators. Certainly, in the offset world, there is dependency on good after-sales service which is addressed by programs such as Heidelberg’s System Service but, the day-to-day operation of offset presses is still very much under the control of the customer. Not so with digital.

With digital, the sale model differs from a buy/lease one with asset depreciation; to a finance facilitation model where the vendor depends on customer retention as the agreement draws to a close, by upgrading them to a newer model and rolling-over the finance arrangement. However, the big difference is that the finance model is linked to usage – average monthly volumes or the ‘click’ charge to give it the vernacular title.

Screen's Truepress Jet 520 released in 2006 is not sold on a 'click' use basis and, strongly built, retains its value better. Most original 520's are still in use today, 10 years later.

Once you separate the digital press from all of the other benefits that come from the vendor, you have an asset of greatly diminished value. If the press is 5-7 years old or older, you are also exposed to termination of parts supply as the vendor frees up warehouse space by turfing out all remaining parts for that particular model, or selling them to after-market support companies.

There are exceptions to the ‘click-finance’ sale model. France’s MGI sells its Meteor presses as stand-alone machines; Kodak’s NeXpress has been sold on a consumables-use basis for years and Screen sells its Truepress Jet520 series and L350UV label press without click and the customer buys ink and parts on an as-needed bases. Interestingly, all of the abovementioned machines are more robustly engineered than the average digital press.

While resale prices for offset presses are unquestionably down in today’s market, compared with a few years ago, demand is still high – especially for later model machines with reasonable impression counts and a service history. Again, it’s just like cars. Shorter depreciation cycles can mitigate this to some extent but, when one sees what can be had from an offset vendor in a brand new machine today, buyers are gaining much more value-for-dollar than they were, say before 2000. Thus, it is understandable that resale values are somewhat lower.

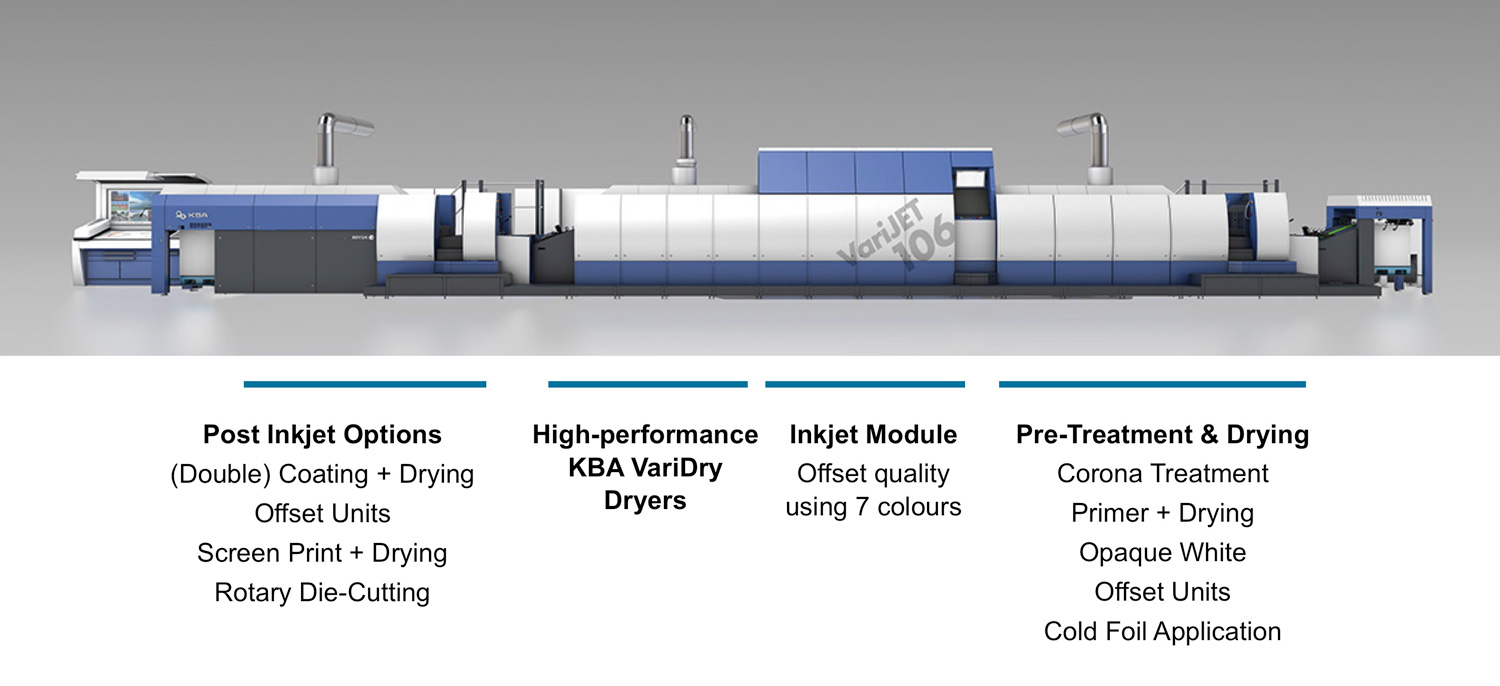

With digital presses moving into B2 and B1 sectors and sporting heavily-engineered sheet handling and finishing; it is becoming hard to distinguish them from big offset presses. KBA’s Varijet 106 for folding cartons looks like a Rapida line but for the 7-colour Xerox ‘box’ stuck in the middle. At drupa, Heidelberg stated that its PrimeFire 106 inkjet press, co-developed with Fujifilm, will not be sold on a click-basis but sold as a press asset.

Landa, whose sheet handling is all-Komori, has a pay-per-use business model so recurring revenue comes in from Nanoink, belts, printheads and parts, but the press is purchased.

Digital presses, if kept and re-sold, need to be sold with some kind of vendor assurance that parts, maintenance, software support and consumable supply will be on-going. This can be either pre-packaged by the seller in consultation with the manufacturer, or negotiated by the buyer. After all, a secondhand buyer of a manufacturer’s machine might represent a future new customer at some stage. Unlike most offset presses, digital presses depend heavily on the relationship with the manufacturer. Some countries, like the USA, have introduced legislation to ‘free up the market’ and allow third-party refurbishment, resale and legally enforceable manufacturer support for used digital presses.

While the A3/B3 press market is dominated by ‘click’ selling, the new breed of B2 and B1 digital presses contain much more metal-engineering drawn from offset presses and thus, we may see a more robust and freer used equipment market develop, once these machines start to find their way onto the pre-owned markets, such as pressXchange of course.